It's been a rough winter in the UK--storms and floods have devastated counties like Somerset. One small positive thing that's come of it all, though, is the curious reappearance of a submerged forest of the coast of Wales:

The earliest account is found in the Llyfr Du Caerfyrddin:

Briefly, a girl named Mererid fails at her duties of keeping the floodgates closed, and the land is subsequently drowned.

There are several Celtic legends like this: Ys at the bottom of Douarnenez Bay in Brittany, Lyonesse in Mount's Bay in Cornwall, and finally Cantre'r Gwaelod in Cardigan Bay, which, as it happens, is the same area as this newly-exposed forest that's been under water for five thousand years.

But this isn't the only lost land found again; a forest was found in Mount's Bay, Cornwall. As the BBC reported:

On the one hand, we can't say for certain that the memory of these lost lands were carried down for thousands of years, but we do know that Britain has been continuously inhabited for at least ten thousand years, since the end of the last Ice Age. It's a leap, but not an entirely unreasonable one, to suggest that the stories later preserved by the Celts were memories of the culture that predated them, passed on, influencing their myths.

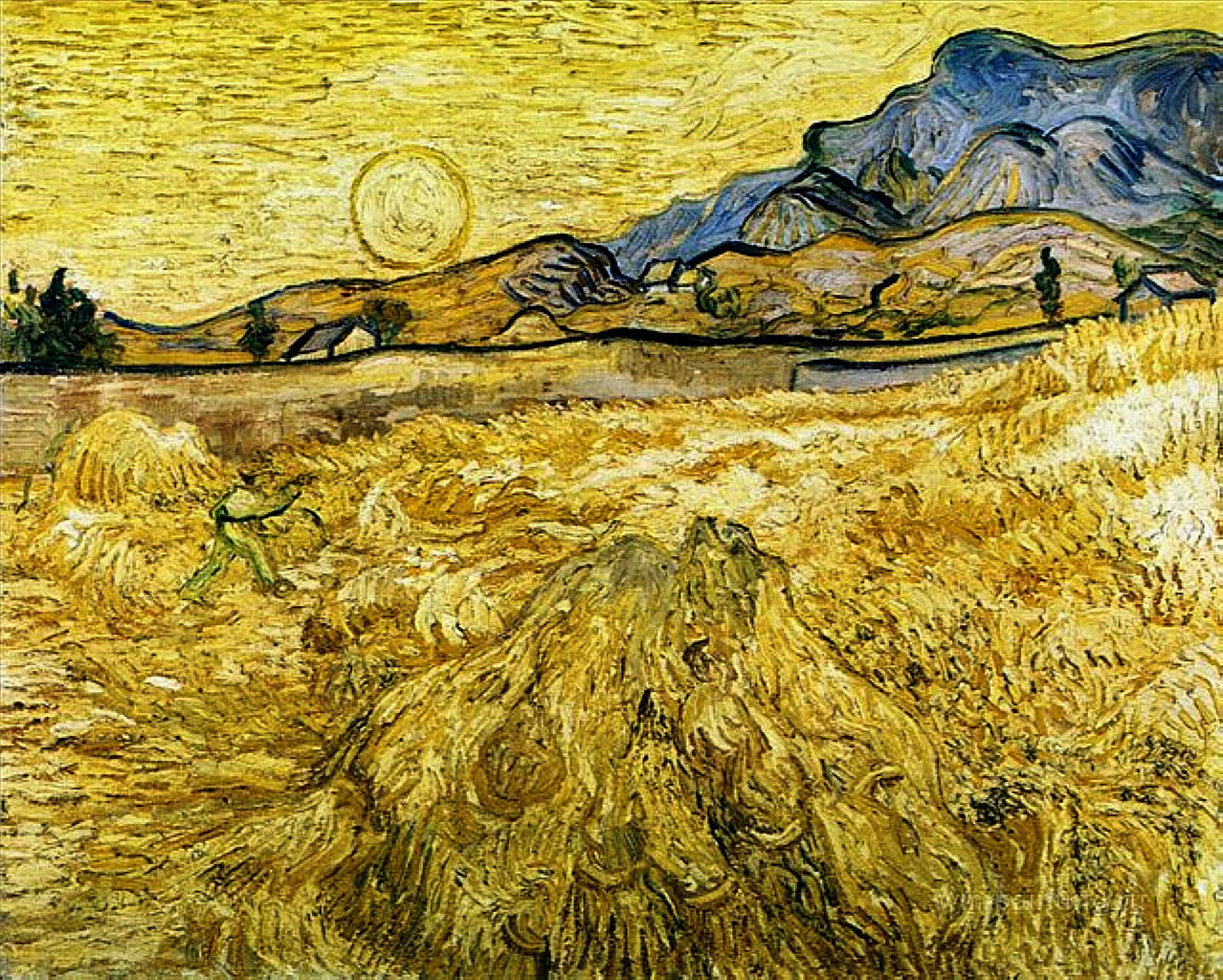

Composed mostly of oak and pine, the forest is believed to date from the Bronze Age. It was buried under a peat bog 5,000 to 6,000 years ago, then inundated by rising sea levels until this winter's violent storms stripped away the covering of peat and sand. The high level of alkaline and lack of oxygen in the peat has preserved the wood in an almost pristine state.

A walkway made of sticks and branches was also discovered. It's 3,000 to 4,000 years old and was built, it is believed, to cope with rising sea levels back then. "The site around Borth is one where if there is a bad storm and it gets battered, you know there's a good chance something will be uncovered," says Deanna Groom, Maritime Officer of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, who helped find the site.But what's really interesting about this is the location of this submerged forest: Cardigan Bay, in the area of the fabled Cantre'r Gwaelod--the "drowned hundred" of Gwyddno Garanhir, a legendary king, who may (or may not) be the same as the historical 6th century ruler Gwyddno ap Clydno of Meirionydd.

The earliest account is found in the Llyfr Du Caerfyrddin:

Seithenhin sawde allan.

Ac edrychuirde varanres

Mor. maes guitnev rytoes.

Boed emendiceid y morvin

Aehellygaut guydi cvin.

Finaun wenestir mor terruin.

Seithenhin, stand thou forth,

And behold the billowy rows;

The sea has covered the plain of Gwydneu.

Accursed be the damsel,

Who, after the wailing,

Let loose the Fountain of Venus, the raging deep.

Briefly, a girl named Mererid fails at her duties of keeping the floodgates closed, and the land is subsequently drowned.

There are several Celtic legends like this: Ys at the bottom of Douarnenez Bay in Brittany, Lyonesse in Mount's Bay in Cornwall, and finally Cantre'r Gwaelod in Cardigan Bay, which, as it happens, is the same area as this newly-exposed forest that's been under water for five thousand years.

But this isn't the only lost land found again; a forest was found in Mount's Bay, Cornwall. As the BBC reported:

Remains in Penzance, Cornwall, can be seen after sand was ripped from beaches by a series of storms which hit the coast in the new year.

Geologists believe extensive forests extended across Mount's Bay in Penzance between 4,000 and 6,000 years ago.

The shifting sands have also revealed wrecks, an iron age settlement in Devon and wartime explosives in Devon, Somerset and Dorset.

Remains of ancient forests have also been seen on Portreath beach, Daymer Bay in Cornwall and Bigbury Bay in Devon.This is the area often associated with Lyonesse, the drowned land that was home to Tristan.

...

St Michaels Mount in the bay is known in Cornish as Karrek Loos yn Koos - which means Grey Rock in the Wood.

On the one hand, we can't say for certain that the memory of these lost lands were carried down for thousands of years, but we do know that Britain has been continuously inhabited for at least ten thousand years, since the end of the last Ice Age. It's a leap, but not an entirely unreasonable one, to suggest that the stories later preserved by the Celts were memories of the culture that predated them, passed on, influencing their myths.